The Science of Warming Up for Irish Dance

How to construct the perfect warmup for class and competition

INJURY PREVENTION & RECOVERYSTRENGTH & CONDITIONINGFEIS PREPARATION

When you watch an Irish dancer fly across the stage, the performance looks artistic and (hopefully) effortless, but physiologically, it’s closer to running an 800-meter race than you might think.

Like the 800m, Irish dancing sits at the crossroads of speed, power, and endurance. It is a hybrid event: highly technical, neuromuscularly demanding, and powered by both anaerobic and aerobic systems. That’s exactly why the warmup is not optional; it functions as both performance enhancer and injury prevention.

Dancers often underestimate just how much of an athlete they are, and how they ought to treat their bodies like a middle-distance runner. Many expect their bodies to perform right away. Others think a few stretches is sufficient. While still others believe they need to follow a long, drawn-out protocol that includes rollers, bands, and light weights demonstrated by their favorite social media influencer and still worry they’re not yet prepared.

Are you confused about how to warm up for competition? Should it be the same as practice? Are you even getting an appropriate warmup for class?

What is the right warmup for Irish dancers?

The answer is that, while it does depend on the event (ie. is it for class or for a competition?), individual physiology, the current state of fatigue and recovery, and age and experience, every warmup should follow the RAMP protocol.

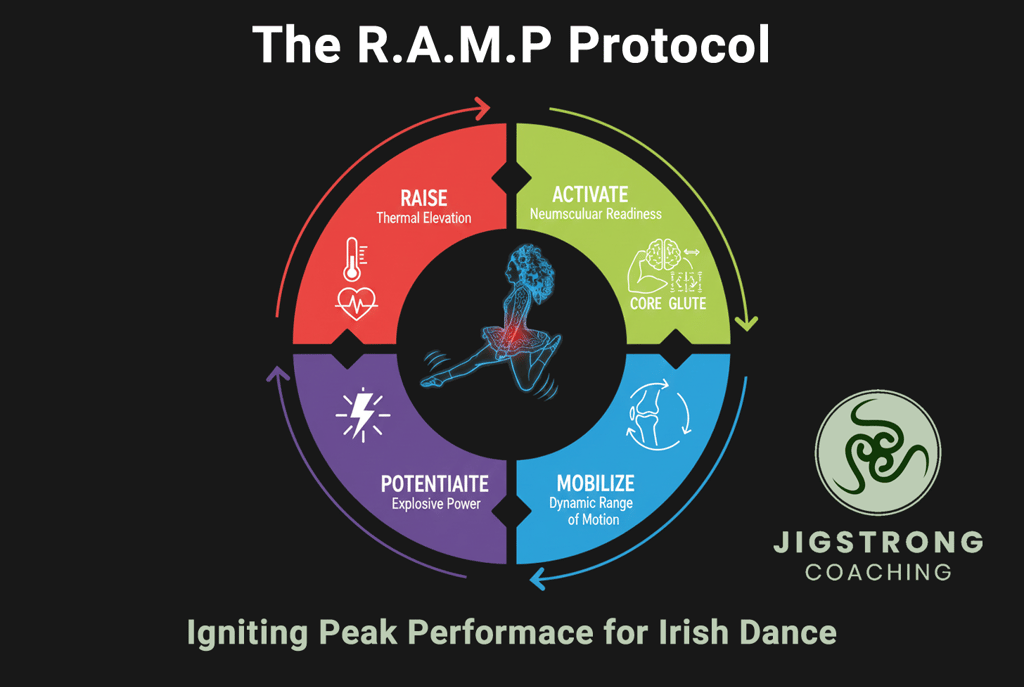

The RAMP protocol is a phase-based warmup system that stands for Raise, Activate and Mobilize, and Potentiate. It is intended to prepare the body for vigorous physical activity.

The Physiology Behind the Warmup

1. Neuromuscular readiness

Irish dancing requires footwork precision, controlled posture, explosive jumps, rapid limb stiffness adjustments, and fine motor timing.

A gradual warmup increases motor unit recruitment efficiency and improves “rate coding,” how fast your nervous system can fire signals to the muscles. Without this, dancers feel sluggish, sloppy, and unstable.

2. Metabolic activation

Dancing full rounds relies heavily on:

Phosphocreatine system (0–10 seconds) for explosive jumps

Fast glycolysis (10–45 seconds) for high-intensity sequences

Aerobic support for longer rounds (slip jigs, hornpipes, and sets), recovery between rounds, and multi-hour classes.

A warmup increases the rate of ATP turnover, priming these pathways so your body can access energy rapidly.

3. Tissue elasticity and force production

As muscle temperature rises, collagen fibers become more pliable, tendons store elastic energy more effectively, and injury risk decreases, especially in the Achilles, calves, pes anserine, and hip flexors (major risk zones for Irish dancers).

R.A.M.P. Phases:

1. Raise — Thermal Elevation and System Activation

This is the cornerstone of every effective warmup. It begins with low-intensity movement aimed at increasing muscle and core temperature. This leads to:

Faster nerve conduction

More efficient muscle contraction/relaxation cycles

Increased metabolic enzyme activity (ATP turnover)

Improved oxygen kinetics

Better tendon elasticity and recoil

Reduced injury risk

Warmer muscles are more elastic, contract more forcefully, and relax more quickly. Without raising body temperature, tissues are not as pliable and motor units are not primed, which increases the risk of strains.

The increase in blood flow delivers oxygen and nutrients to working muscles and removes metabolic waste products more efficiently. This phase is non-negotiable for explosive sports.

2. and 3. Activate and Mobilize — Neuromuscular Stability and Dynamic Range of Motion

Irish dancers rely heavily on:

rapid motor unit recruitment

excellent proprioception

deep-core and pelvic stability

glute activation

ankle–foot stiffness control

Fine motor control and fast foot movements demand a highly “awake” nervous system. This phase activates the small stabilizers and sets the foundation for technique.

Irish dancing also requires a unique combination of:

strong turnout

hip mobility

ankle mobility

upright spinal posture

dynamic leg extension and flexion

Dynamic mobility—not static stretching—is what improves movement quality before a performance. It allows dancers to hit lines and clean beats without losing tension or stability.

4. Potentiate — Explosive Power and Competition Readiness

This is where the warmup begins to mirror the specificity and intensity of dancing. Short, controlled bursts of high-speed movement:

stimulate the anaerobic glycolytic system

improve rate of force development

sharpen timing and rhythm

prepare tendons for reactive forces

increase confidence and readiness

Like 800m runners, dancers must “prime,” not fatigue themselves.

Class Warmups and Daily Training (15-20 minutes)

These are designed to safely prepare dancers for technique work, drills, and moderate intensity dance practice. A class warmup is usually shorter than what is best for competition.

R — Raise (5–7 minutes)

Purpose: elevate heart rate and increase muscle temperature.

Goal: break a light sweat.

This is the most critical phase and the one dancers often skip.

Examples:

Light jog or skipping – 2 minutes

Lateral shuffles – 1 minute

Fast feet in place – 30 seconds

Light jump rope – 1–2 minutes

High knees or marching – 30–45 seconds

A — Activate (3-5 minutes)

Purpose: wake up stabilizers, foot muscles, glutes, and posture.

Goal: Focus on precision, not intensity.

Examples:

Feet:

Foot articulation and ankle circles

Relevé holds and pulses

Short-range calf raises

Toe scrunches and foot yoga

Quick ankle hops

Hips and Core:

Clamshells or standing turnout pulses

Good mornings

Glute med activation (side steps or banded step-outs)

Glute bridge

M — Mobilize (3-5 minutes)

Purpose: improve dynamic mobility while preserving tension and stability.

Examples:

Dynamic Mobility Drills

Leg swings (front/back + side)

Lunge with twist

Hamstring sweeps

Hip circles

Cat-cow or spine articulations

Avoid static stretches that last longer than 15 seconds; save long holds for post-workout.

P — Potentiate (3-5 minutes)

Purpose: activate anaerobic pathways and central nervous system; access power, sharpen, and ready without fatigue.

Examples:

Vertical hops (low → medium)

Light single-leg jumps

8-16 bars of a dance at 10-80% effort

1–2 short bursts of a key step at 70–90% effort

1 step near-performance effort

This is identical to the “strides” runners do before racing. Dancers should feel awake, sharp, and powerful. The muscles should be warmed and excited, not fatigued or heavy after this phase.

Competition Warmup (20-35 minutes)

This warmup is more extensive and is aimed at peak performance.

R — Raise (5-10 min)

A — Activate (5-8min)

M — Mobilize (5-8 min)

P — Potentiate (5-10 min)

The goal is high-intensity nervous-system priming.

Rest 2–3 minutes before performing. Revisit the high knees, leg swings, mobility, and some light bouncing, such as butt kick jumps, to maintain muscle temperature between rounds, and when you are one dancer 2 dancers out from going on stage.

The Takeaway

You do not need a very long warmup for class. Some dancers warm up quickly and are ready to go in 5 minutes and some do need a bit longer. But because class will take you through skips and jumps, you want to just be warm enough to begin them.

Sometimes if a dancer is taking longer than 10-15 minutes to feel snappy, it is actually an indication of fatigue and that their muscles are not fully recovered. This means the dancer might want to take it easy or, perhaps, even need more calories! The body has energy in a fed state. Being underfueled leads dancers to be in an energy deficit, which will prevent adaptation and adds more stress to the system.

For competition, there is not a long class at the end of the warmup. It is the moment you need to perform your best. This is where a longer warmup is necessary. It does not need to be a full 35 minutes! But you should take at least 20 minutes to gradually turn on your body’s systems and feel sweaty and warm and ready to go!

Lastly, beginners and youths have different needs than adults and elite dancers. Beginners and youths can get away with slightly shorter warmups, while more advanced dancers and adults need more time to be fully prepared for intense work. This requires some trial and error and/or the guidance of an experienced coach to tailor the warmup to you, the individual.